admin

RYERSON WOODS – Brushwood Center at Ryerson Woods is honoring Paul Nicklen and Cristina Mittermeier, two of the world’s most celebrated photographers and conservationists, with the 2022 Distinguished Environmental Leadership Award at the 39th annual Smith Nature Symposium Awards Ceremony at Brushwood Center.

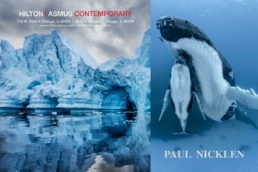

The ceremony will be Sept. 30. In collaboration with Hilton Asmus Contemporary Gallery, their work will be on exhibition at Brushwood Center’s Gallery from Sept. 12 through Oct. 30.

“We are humbled by both Paul and Cristina’s significant accomplishments on behalf of people and the planet, embodied through their stunning artistry, bold leadership and advocacy for the environment,” said Gail Sturm, board chair at Brushwood Center at Ryerson Woods. “We are so inspired by their storytelling, incredible body of art and their advocacy for ocean protection through their nonprofit, SeaLegacy. Their passion for this planet and belief in the power of people to come together and create change is kin to the spirit of Brushwood Center.”

Brushwood Center at Ryerson Woods works collaboratively with community partners, artists, health care providers and scientists to improve health equity and access to nature in Lake County and the Chicago region. Brushwood Center engages people with the outdoors through the arts, environmental education and community action. Brushwood Center’s programs focus on youth, families, veterans and those facing racial and economic injustices.

Nicklen is a Canadian photographer, filmmaker and marine biologist who has documented the beauty and plight of the planet for more than 25 years. He was inducted into the International Photography Hall of Fame in 2019 and in that same year was appointed to the Order of Canada. He has done 23 assignments for National Geographic and won many prestigious awards.

Mittermeier is a world-renowned conservationist and photographer who knows that stunning visual storytelling is the key to unlocking critical action to help heal the oceans and save the planet. She founded the International League of Conservation Photographers in 2005, is a contributing photographer at National Geographic and was named one of the 100 Latinos Most Committed to Climate Action in 2021.

Working together on the front lines of conservation, often onboard the SeaLegacy 1, Nicklen and Mittermeier also are partners in life. Both are marine biologists, and earlier this year they received an Honorary Doctor of Fine Arts, Honoris Causa, from Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, Canada. In 2014, they co-founded SeaLegacy, a nonprofit organization that propelled ocean conservation onto the world stage through the power of visual storytelling, impact campaigns and the funding of sustainability projects. Guided by science and driven by purpose, SeaLegacy is the global marketing, education and communication agency for the ocean.

“To be recognized by Brushwood Center at Ryerson Woods and to be acknowledged alongside people whose work inspires us greatly is a true honor,” Mittermeier said in a news release. “Paul and I look forward to sharing our work, our vision and our dedication to using the authentic beauty of art and storytelling as an invitation to take action to protect our one and only home. We know that Brushwood shares this mission with us and that working together is the only path to true and positive impact.”

The Distinguished Environmental Leadership Award was first presented in 1984 to Roger Tory Peterson, the esteemed American naturalist, ornithologist, artist and educator.

The awards ceremony takes place at the Lake County Forest Preserve’s Greenbelt Cultural Center in North Chicago, a green building and gathering space designed by environmental architect Bill Sturm.

Brushwood will display selections from the couple’s newest exhibition “Evolve, The Photography of Cristina Mittermeier and Paul Nicklen.” As the world and its inhabitants adapt with the ebb and flow of constant change, so, too, does an artist’s view. From a bird’s-eye view of the meandering formations of the Colorado River that mimic patterns of branching trees and human lungs to the lushness of what looks like an underwater painting celebrating the layers of life beneath the water’s surface, all is connected. “Evolve” is the artists’ journey as witness and passionate defender to the natural resilience and determination of a planet on which all life must coexist.

“Evolve” includes the first selections from Nicklen’s new Delta Series ahead of its premier at Art Basel in Miami later this year. It also includes never before seen work from Mittermeier.

September 2, 2022

Language and Perspective: An Interview with Osama Esber

Osama Esber, born in Jableh, Syria, is a widely published author of poetry and short stories. He currently lives in exile in the United States. Esber has published five volumes of poetry in Arabic and has recently begun to write and publish poems in English. He has also been an active and prolific translator of works by Henry Miller, Toni Morrison, Michael Ondaatje, Noam Chomsky, Seamus Heaney, Nadine Gordimer, and Raymond Carver. Since moving to California, he has become a skilled photographer, producing powerful and unexpected images.

By Sophia Maas

You’ve translated many works into Arabic, so my first question is: Why translation? Who are you hoping to reach?

Translation, for me, is about learning. Of course we could talk about words as a source of income, but this is something else. I would like to talk about translation and how I approach it. By translating a book, for example from English into Arabic, you learn from it. You help a general readership get access to a different culture and a different experience of reading. I always learn from writers. For example, when I translated Raymond Carver’s work, I was able to understand things from a different perspective. When people talk about Carver’s work, they call his work “dirty realism.” I don’t like that term. He and other writers have opened my eyes to the richness of language. You find some people write fiction with the spirit of poetry. You find people open up to the experience of poetry. When I translate other people into Arabic I have to ask myself how they see their own world.

Writers learn from each other. I remember when I translated Raymond Carver I had a lot of feedback from other short story writers. They said it was helpful even for them to learn more about the art of short story writing. Translation for me is the noblest way to cross borders. What we know about each other comes through the media. Media is concerned with the political, and certain things don’t come through that as it can through short stories. You can gain a deeper understanding of the essence of American culture — what I consider to be creative literature — and can cross borders and get rid of prejudice and see culture through a deep lens of communication. It is a kind of understanding of one another. Translation can be defined as a deeper tool of communication.

What draws you to translate certain works and not others? What was your favorite work to translate?

This is an interesting question. Sometimes when we translate we are controlled by the market. When I was living in Syria I had a friend with a publishing house. I was at the beginning of my life as a writer, and I was studying American and English literature at university. I had access to writers who write in English, and I always like to choose a book that I like. But the question is why do you like the book? It helps you understand reality from a different perspective. Writers always talk about reality from an unfamiliar angle, and it always fascinated me. I always wanted to translate a work that moves in the same direction. I can mention two books that move in this level. One is The English Patient by Michael Ondaatje. I translated the book before it became famous, so I can say that I translated it because I like the way it tells stories in a rich and powerful way. I also enjoy a book called Einstein’s Dreams by Alan Lightman. It was written by a scientist who became a novelist. The way the book was written, by a scientific mind, has powerful imagination behind it. The language was amazing and evocative. It’s one of the reasons I choose certain books to talk about. This applies also to another publisher who bought the rights to publish the complete fictions of Raymond Carver. I translated the first book, Cathedral, because it can teach fiction writers to think of the world in unique ways. It can help writers understand the process of fiction and the creative writing that goes into fiction. These are the motives behind my choices of translation.

What do you want to say that you feel can’t be said in any way but through poetry?

For me, poetry is not about what I feel directly. What I feel personally is something personal. When we read something like T. S. Eliot or Mary Oliver we feel that the emotion expressed in the poetry is ours. It means that poetry is not about personal direct emotions but collective emotions. This means, for me, that poetry is a vision. René Char says that poetry is always a search for a word that always needs to be searched for. T. S. Eliot says, “I’ll show you fear in a handful of dust.” He talks about his view of the collapse of civilization. It’s said in a vertical way, not a horizontal way. For me, poetry is not always about the self. It is also about the other. What I want to do in poetry, personally speaking, is to be able to write and explore myself, but within a collective context in an unprecedented way. It is difficult to describe how this may happen. Poetry is about how you use language, the styles you use that no one else is using. It is about the difference in style. Compared to prose and other literary forms, poetry is a form to go beyond the norm and the known. It goes beyond the limits of a certain language. If I can talk about love in a way that no other poet has talked about or make it unfamiliar, then that is what I want to do. It is always a search for the things you are unable to say in normal language or the familiar language. No matter who reads a poem, they will find something personal in it. The personal is always in poetry, because it is your personal way of writing. That is your style. The personal is very important in poetry.

Your poetry is in both Arabic and English. How do both languages compliment or limit your artistic or poetic expression?

I originally write my poems in Arabic. I don’t write my poetry in English. As a writer I only find myself in Arabic. It is the language of my blood. I cannot write poetry in English originally. Language is about culture and the mindset through which you see the world. I see myself in Arabic. I can be more creative in it, not because it is more important than English, but because I was born there, and English is a language I have learned. I learned English because of translation. Sometimes you get a chance to be known in a foreign language, though it is not easy.

I saw that you’ve recently gotten invested in photography. What are you trying to express through photography? Is it another avenue of storytelling for you?

There’s a story about my interest in photography I would like to tell you. In 2013 I was living in Chicago and I was invited by the Italian renowned artist Marco Nereo Rotelli who had an installation at the time called Light and Sound. The idea was to transform the facade of the Field Museum in Chicago into a poetic image of Dante’s Divine Comedy. He invited a number of poets to write poems inspired by the Divine Comedy. I wrote a poem about the Syrian war and the hell it created, and when we met later for dinner, he looked at me and told me that I should take photographs and write poems about them. He talked about the relation between poetry and photography and writing poems inspired by photos. I started trying and I found that I related to photographers. I started looking at the visual world in a different way. Anyone can take a photo now. Anyone can press a button. But that is not photography. To take an artistic photograph there is an inspiration, something I can’t define in realistic terms. I can’t see it in the normal state of walking around. Capturing a good photograph is like writing a poem. It is a fleeting thing that you have to capture. In photography, like poetry, there is inspiration. It’s more technical, but it’s still about inspiration. I believe the most important thing about photography is the eye and how it sees things. I’m working on a photographic project about Chicago. You are a wanderer with your camera, you think of things as a photographer. I’m planning my next exhibition and working on it. On my Facebook, when I post a photo, I also write a poem about it. Photography has helped me in a way move away from trying to rationalize things logically. The photograph has saved me from being trapped under the influence of great literary giants. It helped me see poetry in a different way.

What do you find most inspiring about your current work in progress?

What I find interesting and inspiring is the struggle to achieve it. I’m working on poems right now that I feel needs more work. There’s a feeling of imperfection that motivates you and makes me excited about going back to rewrite. There’s a lot of confusion, but when you work, it starts to make sense. Arabic has a tradition going back more than two thousands of years of poetry being a high status symbol. To have a foothold here, to be regarded as a good poet, is something that happens after a long process. You have to struggle with language, you have to write and rewrite. This process makes the magic of writing, and that’s what I think is interesting about it. Something else, now that I live in the United States and my country is too far, this feeling of distance is also very interesting. It helps me see things in a different light that I was unable to see when I was living in the culture.

What keeps pushing you to create?

It’s the feeling that the great book that I’m dreaming of is not written yet. In a sense, writing is an act of searching for perfection. But writing is always related to imperfection. When you write a poem or a book you ask why because you always have more to find that you haven’t expressed before. What evades me is the perfect book. I look at what I’ve written and I think that it’s not what I want. It creates a justification for the act of writing for me.

Why do you think people should keep trying to tell stories or write poetry?

I like this question a lot, actually, so I’ll tell you a story. A famous Arabic book, Arabian Nights, tells the story of the king Shahryar. The king, after discovering his wife has been unfaithful, kills her, and kills those whom she had been unfaithful with. He starts to hate women because of it, marrying and killing a wife each day until there are no more candidates. The minister in charge of marrying the king has two daughters, one of whom is trying to get the king to stop killing his brides. She devises a scheme and convinces her father to marry her to the king. She crafts a story of something she continuously works on, and the king decides not to kill her because he is interested in what she’s creating. She tells interesting stories, yet always keeps them incomplete. I think this is about the power of telling stories. They can prevent death or delaying it. We should keep telling stories to overcome our fear of the unknown, or to enrich life, or to discover the deep parts of ourselves. We travel through deep parts of ourselves. It is a way of creating deep connections between cultures. Here, also, is the importance of translation as well as telling stories.

Sophia Maas is the 2021 In Process intern. She is preparing for her graduation while carving out the time to help new writers develop self-confidence, create her own stories, and find inspiration in more experienced writers.

August 11, 2022

Saviors of the Nomadic Spirit

Osama Esber is a Syrian poet, short story writer, photographer and translator who presently lives in California. He is an editor in Salon Syria, Jadaliyya’s Arabic section, and an editor in Status audio magazine. Among his poetry collections are: Screens of History (1994); The Accord of Waves (1995); Repeated Sunrise over Exile (2004); and Where He Doesn’t Live (2006). His short story collections are entitled The Autobiography of Diamonds (1996); Coffee of the Dead (2000); and Rhythms of a Different Time (in process). He has translated into Arabic works by Alan Lightman, Richard Ford, Elizabeth Gilbert, Raymond Carver, Michael Ondaatje, Bertrand Russell, Toni Morrison, Nadine Gordimer, and Noam Chomsky, to name a few. He attended the international writing program in Iowa in 1995.

By Osama Esber

Writing as a creative art, in its essence, is an act of immigration. This is because a creative artist always searches for a new way to express his or her vision in a new form. This act of searching means that the poet migrates from the familiar to the unfamiliar, from tradition to the horizon that his individual talent expands The process of creative artistic experience is defined by this act of migrating.

The manifestos of great literary movements have always endorsed the desertion of outmoded, traditional, and inherited forms, and the pursuit of novel, innovative means of expression. Nevertheless, new creative forms were always received with suspicion; they were censored or burned, rejected or confiscated in a similar manner to how refugees or immigrants were stuck at borders, isolated in ghettoes, looked down upon, or discriminated against.

The great modern cities and civilizations were built by immigrants or by invaders who became settlers after massacring or marginalizing natives. Nonetheless, this act of invasion, of colonization, is not the topic at hand. What I want to emphasize is that the act of immigration inhabits our entire human endeavor and has defined it since the beginning of creation. Even in religion, the first man migrated (as a result of exile) from the heavens, wearing the mask of the fall, or the first sin.

We have been immigrants since our ancient African ancestors decided to find a haven in which humankind could continue to prosper. Modern anthropology, according to Bill Bryson in his book A Short History of Nearly Everything (Broadway Books 2003) was built around the idea that humans emerged from Africa in two waves. Scientists argued that people have long been migrating and sharing genes as well as information. But humans, who are immigrants in the existential sense, have become citizenry with privilege and power, and have given up their previous role as the saviors of migration as a creative option to enrich and prolong human endeavor. To satisfy their egos, they built refugee camps, regarded immigrants as numbers, taxpayers, or voters and created programs for refugees and asylees, funded fences and walls, created humanitarian relief agencies, and became donors or symbols of charity. Power is highly skillful and cunning in crafting and donning masks.

For the current power structures that dominate the world, Africa, the continent from which the first immigrants left, was only a source of slaves and refugees, epidemics and mines; Arab countries are markets and oil wells; Latin American countries are the spring of cheap labor and the dump for industrial waste. Inhabitants of other countries and the children of other cultures were not allowed to taste the bread of modernity, but sometimes were allowed to eat the crumbs that fell from the tables of their supposed masters.

People feed on oblivion and develop a short memory, a memory that betrays history and experience. People forget that they have been immigrants since the first humans migrated to a new place. We live in an age of disconnection and isolation. Politics, as practiced in the world, continue to pave the way for disaster. The gap between misery and privilege expands, technology still under the control of Cain, the slayer of his brother. The story originated and continues from a crime that has disguised itself as progress. Brothers have forgotten that they are related, blinded by greed and the desire to dominate nature.

The human nest, the only haven for us, we the migratory birds of creation, has been disturbed. New developed powers of evil and darkness have been released. The main concern, as usual, has been what should be done to make businesses thrive and large companies continue to operate. We should give money to people so that they can make purchases. The market should not stop. Consumers should remain activated. Concern for the market’s continuous immunity has required taking care of human subjects.

In the Arab world, where the future is as murky as London’s fog, governments behave as if there is no epidemic. Money is not for taking care of people; money is for buying from the West more gears to control people, or for depositing in private Swiss banks.

In the beginning, regimes were relieved by the pandemic. The dark forces of nature were in the service of despotism and autocracy; no one dared to assemble or to go out onto the streets. But as despair continued to reign, and corruption soared to new heights, people challenged the pandemic as well tyranny, and went out to protest because their livelihoods had been stolen and they were deprived of a life with dignity and respect in the miserable cities of the Middle East. These are cities without hope, where one can “show you fear in a handful of dust,” as T.S. Eliot stated in The Waste Land, or in any face. This is not only the fear of losing your job that Eduardo Galeano discussed in his book Upside Down: A Primer For the Looking-Glass World (Metropolitan Books 1998), but also a fear of losing your meaning and purpose, of reaching a point where you find yourself chanting T.S. Eliot’s lines in The Hollow Men, “We are the hollow men/the stuffed men.”

Living in the West is no longer as it was. It may not be as promising as before. It is no longer a rosy dream, contrary to what lines of people at the gates of foreign embassies in the Middle East or at border crossings, or anywhere, think.

Once upon a time, and a good time it was, Arab writers used to visit Western capitals and return to talk about the wonders of modernity, philosophical theories, and great literary and intellectual movements, but now Arab writers come to stay, not to return and tell their stories like the great travelers of old times. They run away from tyranny and bring with them their countries in a metaphoric form, recreate them in language or in dreams, and live in an imagined geography, while in the real geography of isolation they face a double estrangement: They become separate from their roots and victims to a culture of fear, expressed by the established citizenry, who have forgotten their roots, their essence as immigrants who built civilization.

When drought afflicted Syria it led, along with much else, to a tide of uprisings, where the poor and downtrodden went out onto the streets demanding bread, water, and freedom. Now, those who did not die there under bombardment have become immigrants, refugees in neighboring countries where racism bares its teeth. Many of them live forgotten in tents at the borders, while scores of others are under the threat of deportation, which makes evident the narrow limits of human solidarity.

In the light of all this, writers, poets, and artists, the saviors of the nomadic spirit of the human race, should always be ready to forge again- borrowing from James Joyce- in the smithy of their souls the uncreated conscience of their races. They should enlighten their people to the fact that there is only one race on this planet, whose short experience, or journey in a caravan of various magical colors, may come to an end, whose migratory spirit may extinguish and may not find another place to reemerge. It is time to dismantle the barbed wires of our hearts. Climate change and its implicit and explicit dangers should make us think of immigration in a creative way. But the big question is: When our poor planet becomes unable to sustain life, will there be any future anthropologists to discuss another migration?

Cities That Visited Me*

-1-

I saw dolls on your streets

becoming women

and despair stumbling along

like the feet of Syrian workers.

-2-

Sometimes your banks

inject the day’s veins with hope.

Sometimes your dawn

breathes in the smoke of words.

-3-

Your TV channels told us

of other doors,

but when opened,

they only led to another room

in the same house.

– 4-

I saw you a bridge

hanging in the void of your myths

and Mediterranean illusions.

-5-

In your cafes

modernism is smoked

like Cuban cigars,

their leaves smoothed on the thighs

of a professional moment

in a prostitute’s dress.

-6-

I saw books get botox

to seduce their readers.

Your newspapers do not read your mind

your cafes do not change

the wheels or the oil of their language’s engine.

Billboards in your streets wear

naked thighs and bosoms

that relax on sandy beaches.

In their bronze complexion,

we read about a future

that immigrated to other countries.

-7-

The difference in the value of foreign currency

assumes the job of angels

and opens momentarily the doors of paradise.

-8-

I see your face

on an airport’s electric door,

or on a passport stamp,

from which two eyes,

on whose balcony police dogs sit,

look.

-9-

Beirut,

where the borders cross

I saw men made of barbed wire

imprisoning the horizon

inside the pupils of their eyes.

-10-

You are visiting me now,

I wish I could settle you in my language,

I wish I could give you a room

and invite you to a glamorous evening.

I wish I could let you lie naked

on my bed between my arms.

Beirut,

you do not need to forgive me,

I do not fall in love easily with Arab cities,

watching their bellies dancing

with the belt

of death, poverty, tents, and slums

wrapped around their naked waists

does not excite me.

The clock lost its handles.

It looks featureless,

like your soul,

it has lost the road to a body.

* From a divan in process with the same title.

August 11, 2022

$90,000 a Day for One Photograph? David Yarrow Doesn’t Blink an Eye.

The British photographer, known for cinematic set pieces, discusses his iconic images, navigating art and business, and the one thing you should never call him

By Josh Sims

David Yarrow isn’t ashamed about making money — a lot of money — from his photography. And that’s for deeply personal reasons.

“One thing detractors say is ‘yeah, well, Yarrow, he’s not a photographer, he’s a businessperson,’ and that doesn’t hurt me at all, because one of the problems with the creative arts is that creatives don’t have a business mentality and that’s dangerous,” the affable, straight-talking Scot tells InsideHook. “My mum was an artist and she went bust because she didn’t care about the business side. One of my mentors says, ‘It’s not creative if it’s not commercial,’ and there’s a lot of truth in that. There’s false pride in poverty in the arts.”

Yarrow started out as a sports photographer — he took that shot of a triumphant Diego Maradona, held aloft by his teammates at the 1986 World Cup — decided he wasn’t so into it, went into banking and launched a hedge fund, and then returned to what he decided had really been his passion all along. He effectively reinvented wildlife photography, by being extremely patient and getting dangerously intimate with his subjects, and by offering a fresh, often awe-inspiring perspective that glorified his subject.

“The best pictures you can look at for a long time and show you something you haven’t seen before,” Yarrow posits. But don’t you dare call him a “wildlife photographer.”

“I think wildlife photography has become quite toxic. And if anyone [on my team] calls me a wildlife photographer, they get fired,” the 56-year-old laughs. “I remember talking to the chairman of the Tate and he told me that the one supposed art form that left him cold was wildlife photography. I asked him why and he said, ‘Because I know what a fucking giraffe looks like. I don’t need to be told what a giraffe looks like, and then to be told it’s art.’ It’s not. Go on social media every day and there are all these people on safari in Kenya with long lenses just taking pictures of leopards. That’s not art. All you’ve proven is that you’ve been able to pay to be in a beautiful place, you’ve got good camera equipment and you’ve got lucky.”

Being able to position photography as art, Yarrow says, quite upfront about it, is where the money is. Sure, he has deep affinity for the great outdoors and its inhabitants — a lot of the charity work he does with chums Chris Hemsworth and Cindy Crawford is to raise money to tackle disastrous events like the enormous bushfires in Australia in 2019 and 2020. You can’t not have an affinity for it when you’re face-to-face with a grizzly bear or a lion, he laughs, though he’s always been more worried around people than teeth and claws.

“People can do three things that animals can’t: They can get high — well, actually gorillas can get high too, but not in a bad way; they can get drunk; and they can buy guns,” he says. And that’s a very bad combination.

Yarrow is also very aware that his necessarily pin-sharp shots tend to work particularly well large-scale and that the people with the money to spend on art tend to have a lot of wall space to fill. Just as Jeff Bezos once said he wanted to build the most “consumer-centric” company ever, so, Yarrow jokes, he set out to be the most “wall-centric” artist ever.

Take, for example, his preference for black and white images. This is partly a product of his love of the cinema. Yarrow shoots in color but prints in black and white, because, he says, there’s a timelessness to monochrome, a reductiveness to it.

“Someone said that if you photograph people in color you see their clothes, if you do it in black and white you see their souls,” he says. But also because, in all seriousness, black and white works with anyone’s interior scheme. “Some colors are horrible to have on your wall. Yes, the monetizing is shameless,” he chuckles.

It’s just as well, since he seems to spend it as fast as he makes it. He is best known now for his monumental set pieces — essentially movie productions distilled into one frame — that can cost in the ballpark of $90,000 a day to shoot.

One of his most arresting shots, “Get the Fxxx Off My Boat,” part of a series based around The Wolf of Wall Street, involved catching multiple posed models, a popping champagne bottle and flying dollar bills on the back of a yacht. At sea. With a helicopter hovering overhead. And with, front and center, a real wolf, also posing. None of it is CGI.

That kind of expenditure really focuses the mind, Yarrow says.

“It’s not for the practitioner to call what they do art, but I did see an opportunity in that if the outside world saw my work as art then it would be willing to pay quite a lot for a picture,” he says.

He recalls taking a photograph of a shark attack in South Africa in 2011. It was printed around the world and he thought he’d finally entered the big time. When the check for all the publication rights came, it was around $17,000.

“And I calculated that it had cost me $18,500 to take the picture. So I thought, OK, this is the world’s worst industry,” he says. “But then a lawyer calling himself Jaws phoned and said he wanted a print for his office wall and I sold that one picture to him for $12,000. And that’s when the penny dropped.”

Yarrow spent the next 10 years making connections, showing his work and building a network of some 30 wholesalers around the world to sell it. It may cut against our romantic insistence that artists starve in garrets. Rather, it’s an eminently pragmatic way of getting his prints to collectors — and he now has a lot of dedicated collectors — wherever they and their blank-walled homes may be. And it allows Yarrow to focus on doing what he loves best: taking pictures.

It’s something he thinks he’s always getting better at. He has off weeks, he admits. “But I think you become a better photographer as you get older because [great] photography comes from the soul and your emotions are more mature,” he says.

Or maybe, he chuckles, “it’s just that the cameras are getting better.”

July 22, 2022

David Yarrow and Cindy Crawford

Context - Art Miami

WE ARE PROUD TO PRESENT

I AM OCEAN

VIP PREVIEW TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 30

November 30 – December 5, 2021

Booth B14

I AM OCEAN, displayed at ART MIAMI/CONTEXT (booth #B14) is a celebration, through both photography and sculpture, of the element that composes over 70% of our planet and 70% of our bodies. Inspired by our gallery’s conservationist undertakings, I AM OCEAN seeks to inspire positive change through exposure, displaying the incomparable majesty, depth, and power that Earth’s oceans encompass. It is, ultimately, a reminder that human beings and water exist within a symbiotic realm of one another, and that water is the fundamental essence of life.

General Admission and VIP passes available now.

Please contact us at arica@hiltoncontemporary.com if you would like to attend.

Dear Friends,

It is with great pleasure I invite you to join us for our first major art fair in two years. We are thrilled to participate in the CONTEXT Edition of ART MIAMI.

Opening night is Tuesday, November 30th. If you are unable to be in Miami next week, you can still see our exhibition remotely on Artsy! (We will send you links.)

Our theme this year is I AM OCEAN, featuring works from acclaimed photographers, filmmakers and marine biologists Paul Nicklen and Cristina Mittermeier, co-founders of leading ocean conservancy organization SeaLegacy, alongside David Yarrow (UK) and internationally known artists and sculptors Kostis Georgiou (Athens, Greece), Hugh Arnold (south of France), Sophia Collier (California), David Gamble (UK) Jack Perno (Chicago) and Christian Voigt (Hamburg, Germany).

Cristina Mittermeier and Paul Nicklen will be in attendance for the fair, with an artist talk to follow.

We also be featuring David Yarrows latest recreation of yet another scene from the Wolf of Wall Street film titled, “Get the F***Off My Boat.” Our exhibition will be awash in ocean related imagery. Excuse the pun!

After much planning and praying, we at last received (in the nick of time) two monumental sculptures (an 8 ft Red Diver and a life size Blue Bull with dancer on aluminum (along with a charming Hedgehog and a few other smaller pieces) from our friend and one the most celebrated artists from Athens, Greece, Kostis Georgiou. The sculptures will be exhibited in the Special Projects section of CONTEXT.

If you plan to be in Miami, please reach out to us. We will send you VIP tickets to the show. We look forward to seeing you, either in Miami or back in Chicago.

With my warm regards,

Arica

New David Yarrow exhibit 'Changing Lanes' takes over Hilton | Asmus Contemporary

DeKalb’s very own Cindy Crawford talks recreation of her famous 90s Pepsi commercial

Posted: Oct 11, 2021 / 10:23 AM CDT / Updated: Oct 11, 2021 / 10:27 AM CDT

CHICAGO — A DeKalb-native and one of the world’s biggest supermodel’s was in Chicago over the weekend.

Cindy Crawford, know for fashion, modeling, acting and lots of business enterprises — among them her infamous 1992 Super Bowl Pepsi Commercial was in Bridgeport Saturday night.

Her image in that commercial was recreated by Photographer David Yarrow to raise money for the American Family Children’s Hospital in Madison, Wisc. — where Cindy’s late brother was treated for Leukemia.

Cindy talked to WGN’s Dean Richards about her roots — and the roots of her famous commercial.

New David Yarrow exhibit 'Changing Lanes' takes over Hilton | Asmus Contemporary